Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a genetic disorder marked by progressive muscle degeneration and weakness. It can be inherited, meaning it gets transferred from parents to the child, and is known to be one of the most severe forms of inherited muscular dystrophy. [1] It affects approximately 1 in 3500 male births worldwide. [2]

DMD is an X-linked recessive disorder caused by alteration in the dystrophin gene, which encodes the protein dystrophin. [3] The gene makes a protein called dystrophin, important for keeping muscle cells strong. [4] The mutation of this gene leads to various muscle disorders, and DMD is one of the most common pathologies. [5] Without dystrophin protein, muscles become more easily damaged, leading to weakness and wasting. Over time, muscle tissue is replaced by fat and scar tissue. [6]

The first signs and symptoms of DMD may appear as early as 4 months; most signs develop around 2 to 3 years. [7]

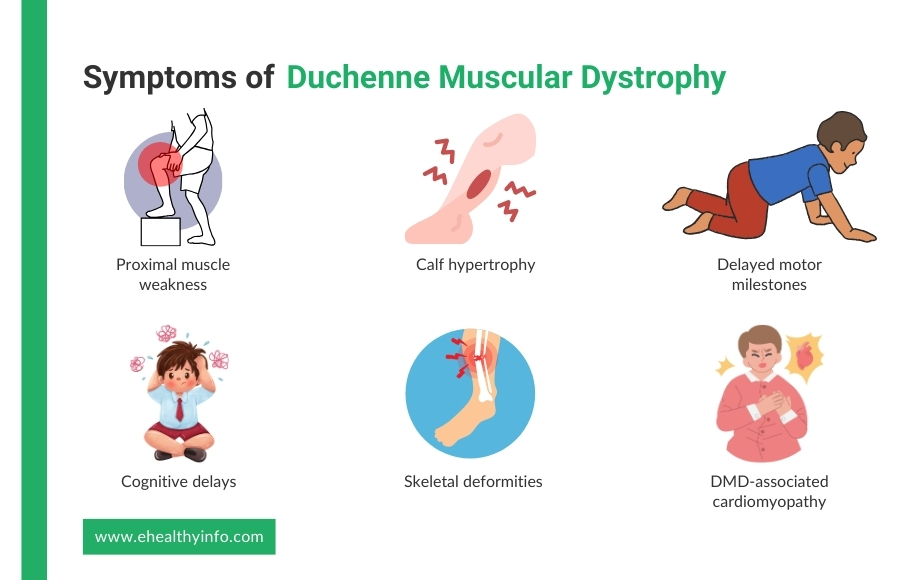

In the case of DMD, muscle weakness selectively affects the limb muscles closer to the trunk. This is known as proximal muscle weakness. [8] The muscles of the hip, pelvic areas, and thighs are affected first, followed by the involvement of the shoulder muscles. Children often exhibit difficulty with activities such as running, jumping, and climbing stairs. [9, 10]

DMD often involves the proximal muscles, resulting in difficulty standing up due to weakness in the hip and thigh muscles. They use their hands to “walk” up their body to compensate. They push off from the floor to their knees and then use their hands to push themselves upright. [11]

In most patients, the calves appear enlarged. This is due to pseudohypertrophy, which replaces muscular tissue with fat and connective tissue. Hypertrophy of the tongue and muscles of the forearm can also be seen, although it is less common. [12]

Children suffering from DMD have delayed milestones such as sitting, standing, and walking. For instance, a delay in the age of first independent walking is common in DMD. [13]

Cognitive delays and intellectual impairment are seen in most people with DMD. Children with DMD experience delays in speaking and other cognitive functions. [14]

DMD can present with low bone mineral density and a higher risk of bone fractures. Moreover, corticosteroid therapy, an authorized DMD treatment, may have a variety of consequences on the health of the bones in DMD patients. [15]

Features of cardiomyopathy usually develop in the early teens. Dilated cardiomyopathy may present with different symptoms, such as persistent tachycardia, signs of heart failure, and arrhythmia. [16]

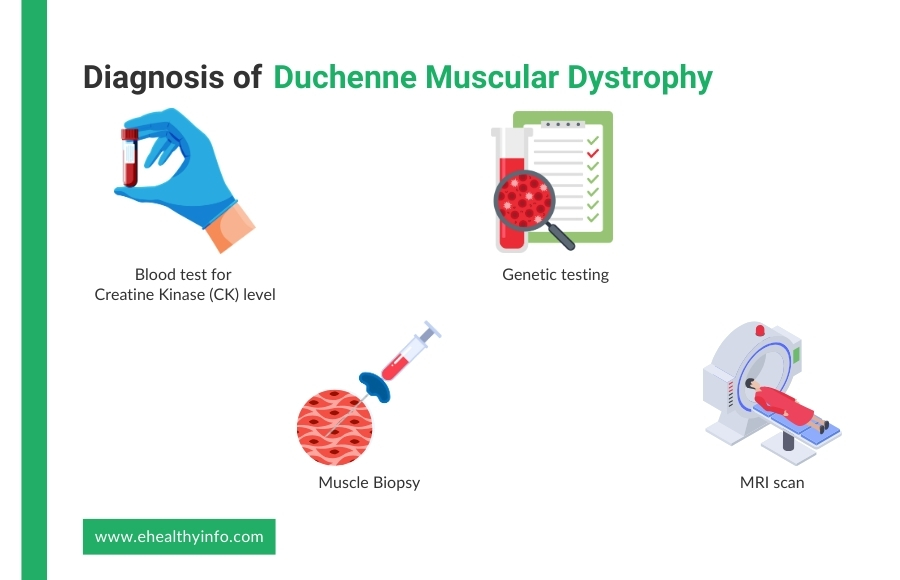

The diagnosis of DMD usually begins with your doctor noticing signs like muscle weakness or delayed milestones, such as trouble walking or climbing stairs. If your doctor suspects DMD, they may start by asking about your family history since this condition is often inherited. They might also perform a physical exam to check for specific signs, like calf muscles that look large but feel weak.

Your doctor may recommend a blood test to measure your creatine kinase (CK) levels to confirm the diagnosis. CK is a protein that leaks into your bloodstream when muscles are damaged, and high levels can be an early clue for DMD. Serum CK is elevated even before the development of clinical features. Levels of serum CK peak by the age of two and are often 10 to 20 times the normal limit. Other muscle enzymes, such as aldolase, may also be elevated. If your CK levels are elevated, your doctor may suggest genetic testing. This test looks for mutations in the dystrophin gene, which is the most common cause of DMD. It’s a simple test done by taking a blood or saliva sample. [17]

In some cases, your doctor might also recommend a muscle biopsy, where a small sample of muscle tissue is taken to look for the presence of dystrophin protein. This is less common now, as genetic testing is usually enough to confirm DMD. If needed, imaging tests like MRI can also help your doctor assess the extent of muscle damage. [1]

Currently, there is no cure for DMD, but it can be managed symptomatically with medications and surgery in some cases.

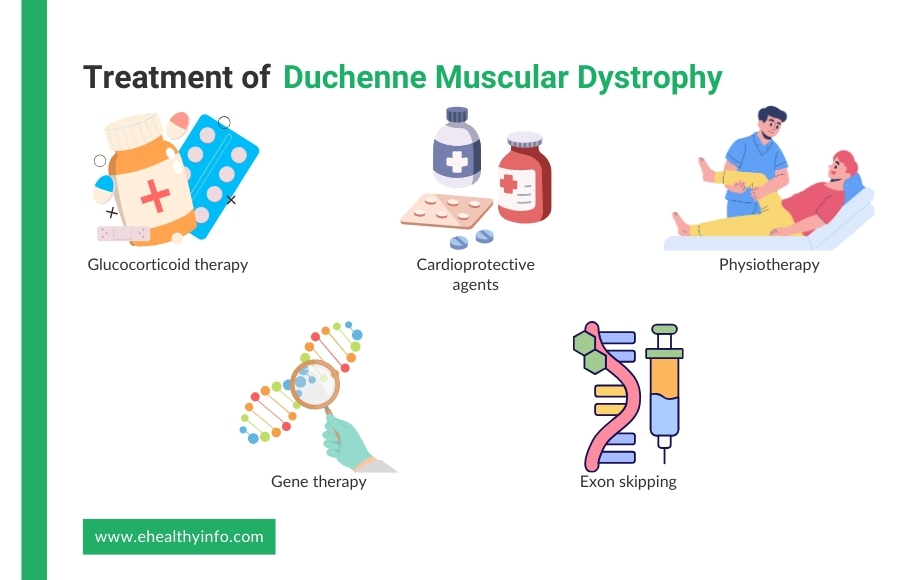

Glucocorticoids reduce the rate of muscle damage. Prednisone and deflazacort have been shown to prolong ambulation and delay the onset of secondary complications. Prednisone is used in patients over four years of age whose muscle function is declining. Deflazacort is another alternative with a better side effect profile. The major side effects of glucocorticoids include weight gain, bone mineralization, and behavioral changes. [18, 19]

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and beta-blockers are used to manage cardiomyopathy. These agents prevent the onset of heart failure. Overt cases of heart failure are managed with digoxin and diuretics. [20]

Physiotherapy is the first choice for weakness. Physiotherapy options are based on the patient’s requirements. In advanced cases with contractures, surgery is suggested. Surgery is also used to correct scoliosis and improve pulmonary function.

Emerging therapies for DMD offer new hope by targeting the root cause of the condition, mutations in the dystrophin gene. Gene therapy is a promising area where scientists aim to deliver healthy copies of the dystrophin gene to muscle cells, helping them produce the protein needed to strengthen muscles. Another exciting approach is exon skipping, a technique using specialized medicines to skip over faulty parts of the gene, allowing the body to create a functional, though shorter, version of dystrophin. Other treatments focus on reducing inflammation and protecting muscle tissue from further damage, such as medications targeting specific proteins or pathways involved in muscle breakdown. These therapies are still being studied in clinical trials, but they represent a big step forward in improving the lives of individuals with DMD. [19]

The prognosis for DMD has improved over the years due to advances in medical care, but it remains a serious and life-limiting condition. DMD is a progressive disease, meaning it worsens over time as muscle weakness spreads throughout the body. Most children with DMD lose the ability to walk usually by the age of 12, the onset of scoliosis around 14 years. They may face complications such as heart and lung problems needing ventilatory support by late teens. The most common causes of death in individuals with DMD are respiratory failure and heart failure due to the weakening of the muscles involved in breathing and heart function. With proper medical management, including physical therapy, many individuals with DMD can live into their 20s or 30s, and some even longer. [21]

DMD cannot be entirely prevented because it is caused by genetic mutations, and about a third of cases happen randomly without a family history of the condition. However, genetic counseling and testing can help identify if you or your partner are carriers of the gene before planning a family. This can help assess the risk of passing the condition on to your child. For families with a history of DMD, prenatal testing or preimplantation genetic diagnosis during in-vitro fertilization can detect the mutation early. [21]