Highlights of Gestational Diabetes

- Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) develops when the body cannot produce enough insulin to meet the extra demands of pregnancy, leading to higher blood glucose levels.

- Women who are overweight or suffer from Polycystic Ovary Syndrome are at higher risk of developing GDM.

- Many women with gestational diabetes don’t always experience symptoms. Every woman should be tested with the glucose challenge test between 24-28 weeks of pregnancy.

- If your baby grows too large or if your blood glucose levels are not well-controlled, a cesarean section may be needed.

- Women who have had gestational diabetes during pregnancy are at a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes later on.

What is Gestational Diabetes?

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a type of diabetes that occurs during pregnancy. It can develop at any time during pregnancy but is more common in the second or third trimester. This happens because your body can’t produce enough insulin, the hormone that controls blood glucose levels, to meet the increased needs of pregnancy. Gestational diabetes can cause issues for both you and your baby during and after pregnancy. [1–2]

Causes of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

During pregnancy, the body naturally becomes more insulin-resistant to ensure the growing baby gets enough glucose. This resistance is mainly caused by hormones from the placenta, which block the action of insulin. Usually, the pancreas tries to compensate by making more insulin to keep blood glucose levels normal. However, in some women, the pancreas is not able to compensate enough, and as a result, they persistently have high blood glucose levels, leading to gestational diabetes. So, women with gestational diabetes have both higher insulin resistance and not enough insulin produced by the pancreas. [3-4]

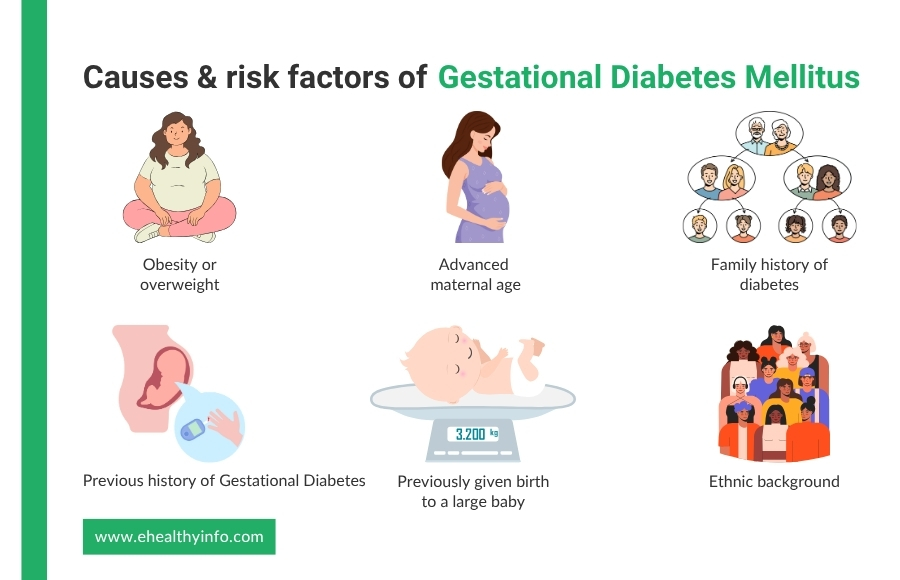

Who is at Risk of Developing Gestational Diabetes Mellitus?

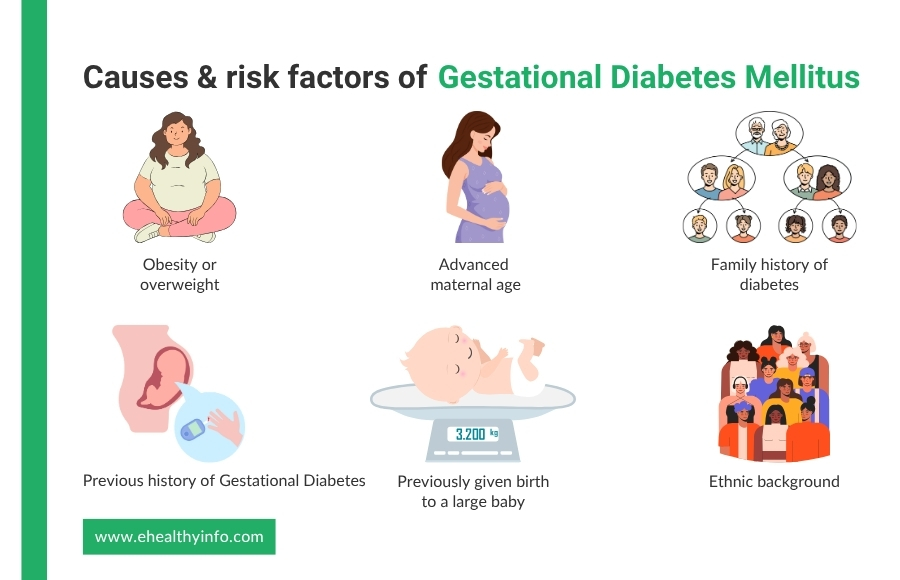

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is influenced by several important risk factors. Below are some of the main risk factors associated with GDM:

1. Obesity or overweight

Obesity is a significant risk factor for GDM, as excess fat causes insulin resistance. A pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m² or higher significantly increases the risk of GDM, especially if you’re not physically active. [5]

2. Advanced Maternal Age

If you are 30 years or older, you’re susceptible to high blood glucose levels during pregnancy. With age, the sensitivity of insulin decreases, and the function of the pancreas also gets affected, because of which older women are more likely to get GDM. [6]

3. Family History of Diabetes

A family history of diabetes further increases the risk of GDM due to genetic factors that affect insulin production and secretion. About 30% of women with GDM have been found to have at least one parent with type II diabetes. [7]

4. Previous History of GDM

If you had gestational diabetes in a past pregnancy, there’s a higher chance it will happen again. This means your body may have difficulty managing glucose levels during pregnancy. [8]

5. Previously given birth to a large baby

If you had a baby weighing more than 9 pounds (4 kg) before, there is an increased risk of gestational diabetes in future pregnancies. [9]

6. Ethnic Background

Ethnic groups, like South Asian, Black Caribbean, and Middle Eastern women, have a higher prevalence of GDM. This has been associated with various factors like genetics, body composition, and gestational weight gain, which differ among different ethnic groups. [10]

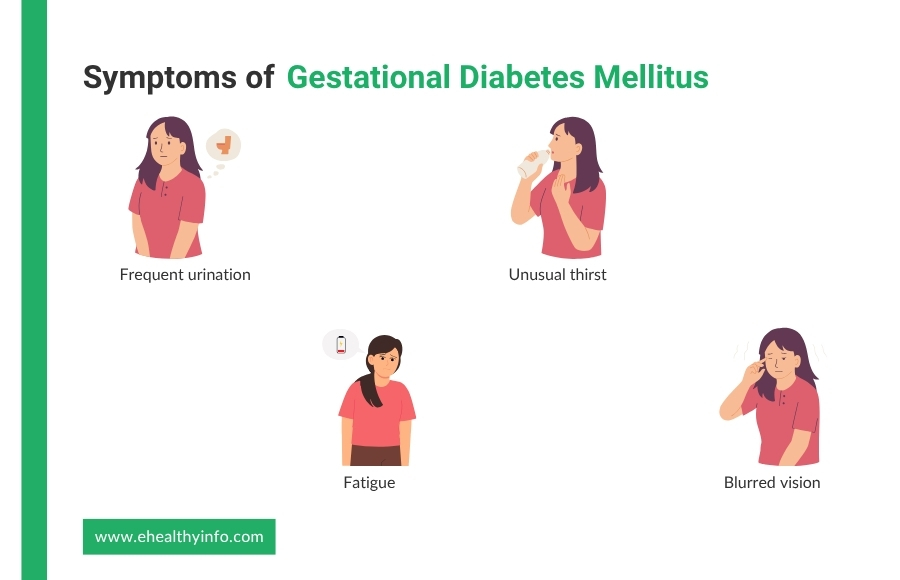

Symptoms of Gestational Diabetes

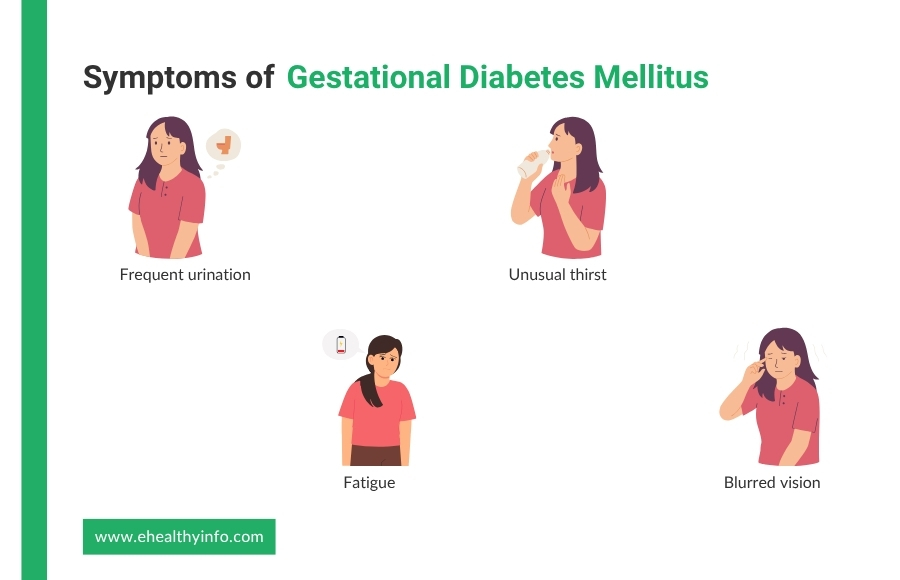

Gestational diabetes often doesn’t cause noticeable symptoms. Some of the symptoms you might notice are:

1. Frequent Urination

You may find yourself going to the bathroom more often. While frequent urination is common in pregnancy, it can be worse if your blood glucose is too high because your kidneys are trying to flush out the extra glucose. [11]

2. Unusual Thirst

You might feel thirsty more often than usual, even if you drink enough water. This happens because high blood glucose levels make your body lose more fluids. [11]

3. Fatigue

Whether it’s high blood glucose, insulin resistance, dehydration, problems producing energy, changes in the way blood flows, or hormonal imbalances, the way an individual feels flat-out tired is one of the common signs of diabetes. [12]

4. Blurred vision

If you have GDM, you might notice your vision getting slightly blurry. This happens because high blood glucose levels can shift the fluid balance in your eyes, temporarily changing their shape and making it harder to focus. [13]

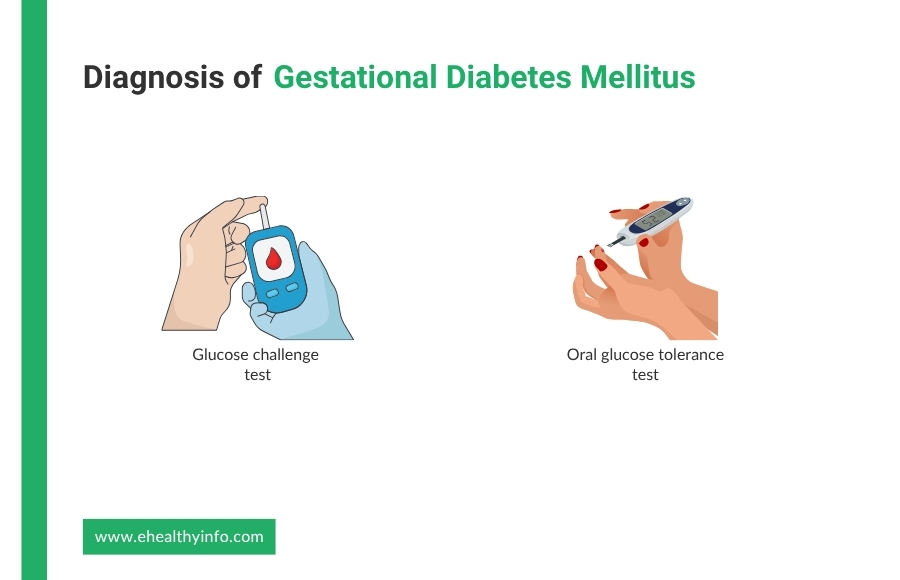

Diagnosis of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

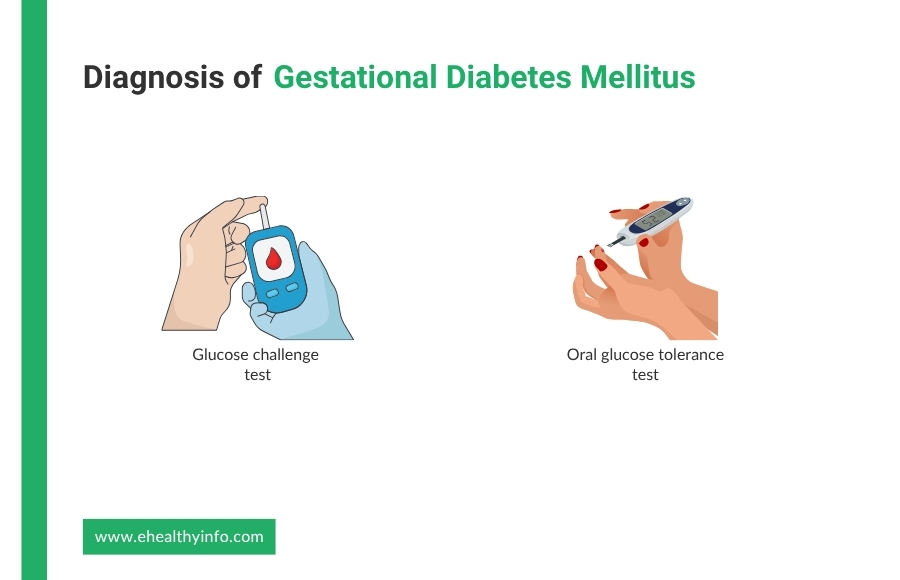

Gestational diabetes is usually diagnosed using a glucose screening test:

1. Glucose Challenge Test

The GCT is a simple routine test to check if you have GDM. This test is usually done between 24 to 28 weeks of pregnancy. In this test, you will drink a sweet liquid with 50 grams of glucose and wait one hour before a blood test. You don’t need to fast before the test. If your blood glucose is below 140 mg/dL, it’s normal. If it’s 140 mg/dL or higher, you may need another test called the glucose tolerance test for confirmation. Since gestational diabetes has no apparent symptoms, this test helps find it early to keep you and your baby healthy. [14]

2. Oral Glucose Tolerance Test

This test confirms gestational diabetes if your GCT shows abnormal results. You will need to fast overnight before the test. First, a fasting blood sample is taken. Then, you will drink a sweet liquid with 75 or 100 grams of glucose, and your blood will be tested every hour for up to three hours. If your blood glucose is higher than normal at multiple time points, it means you have gestational diabetes. The test is usually done between 24 to 28 weeks of pregnancy if your GCT results are high, but if you have a higher risk of gestational diabetes, your doctor may recommend doing it earlier in pregnancy and possibly repeating it later if needed. [15]

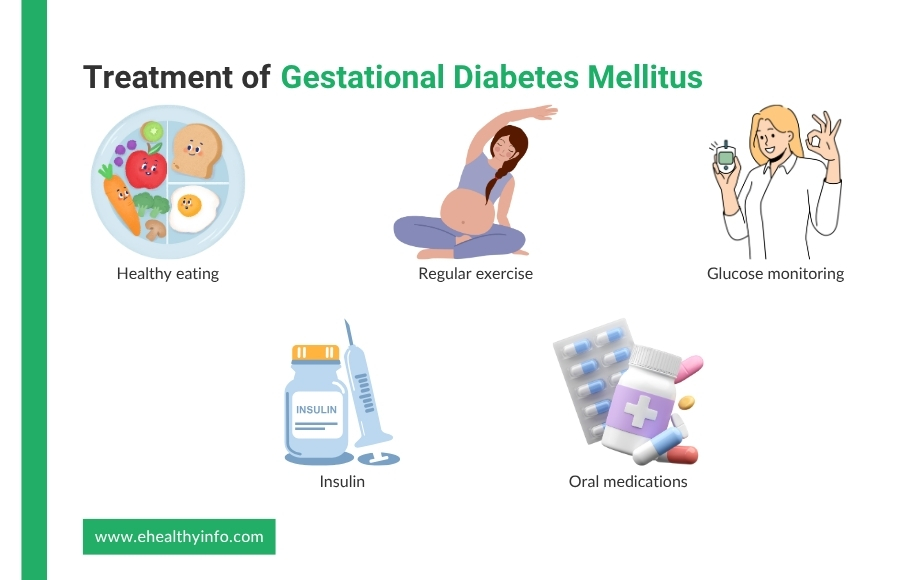

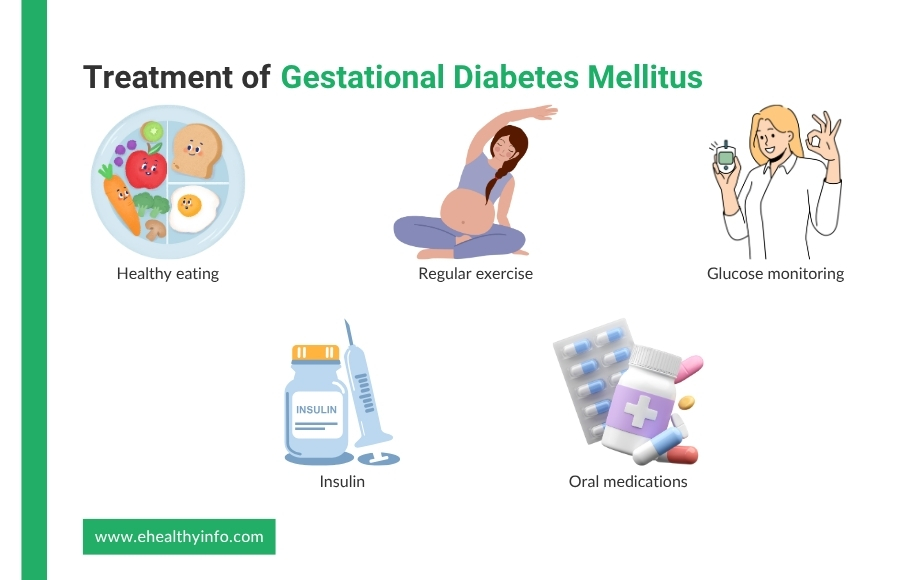

Treatment of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

The goal of treatment for GDM is to keep your blood glucose levels within the target range without affecting the baby and you.

Lifestyle changes

- Healthy Eating: With the right food choices, portion control, and meal timing, you can maintain your blood glucose levels within the desired range. You should go for a balanced diet with whole grains, vegetables, fruits, lean proteins, and healthy fats while avoiding sugary foods and drinks. If you’re not eating enough or if your blood glucose levels are too high, your body may produce ketones. Ketones in your urine or blood indicate that your body is using fat for energy instead of glucose, which can harm both your and your baby’s health. So, you need to eat the right food and in the right amount. [16]

- Regular Exercise: Physical activity can help reduce insulin resistance and control blood glucose levels. However, exercise should always begin with a consultation with your doctor, as you may have other conditions that limit exercise during pregnancy. Your doctor may suggest gentle exercises like walking, swimming, or yoga to keep you active. [16]

- Glucose Monitoring: Regular glucose monitoring is an important part of managing It helps keep your blood glucose levels stable and reduces risks for you and your baby. Your doctor will ask you to check your blood glucose multiple times daily using a glucometer, a small device that measures glucose levels from a finger-prick blood sample. Typically, you will test before meals and one or two hours after eating. Recording your blood gulose readings helps doctors adjust your diet, exercise, or medications. [17–18]

Medications: If diet and exercise aren’t enough, you might need insulin injections or oral medications to help control your blood glucose.

- Insulin: If your pancreas cannot produce as much insulin as is required to keep your blood glucose under control. You might need to take it as an injection. It is given as an injection under the skin, usually before meals or bedtime, depending on blood glucose levels. Your doctor will decide the dose and type of insulin based on your glucose readings. And learning how to inject insulin properly and monitor blood glucose levels is equally important in treatment. Regarding safety, insulin is safe during pregnancy and does not harm your baby. [19]

- Oral medications: Sometimes, doctors may prescribe oral medications instead of insulin to control gestational diabetes. The two most common medications are metformin and glyburide. Metformin helps lower blood glucose by improving insulin sensitivity and reducing glucose production in the liver. Glyburide stimulates the pancreas to release more insulin. Metformin is preferred among these two due to its better safety profile and effectiveness, similar to insulin. While both are effective, insulin is preferred as these oral medications cross the placenta in small amounts, needing monitoring for their effects on both the mother and baby. [20]

Complications of Gestational Diabetes

GDM can cause various problems for you and your baby.

- Complications in the Mother: If blood glucose levels are not well controlled, it increases the risk of high blood pressure, pre-eclampsia (a serious pregnancy condition with high blood pressure and organ damage), and infections like urinary tract or vaginal infections. There is also a higher likelihood of needing a cesarean section due to excessive fetal growth, which can make vaginal delivery more difficult. Also, women with GDM are at a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes later in life, even after the pregnancy ends. [21]

- Complications in Babies: The most common issue of GDM in babies is excessive growth, as high blood glucose levels cause the baby to store extra fat. This can cause difficult delivery, shoulder dystocia (when the baby’s shoulder gets stuck during delivery), and the need for a C-section. Babies born to mothers with GDM are also at higher risk for low blood glucose shortly after birth, as their bodies produce extra insulin to cope with the high glucose levels in the womb. Other potential risks include respiratory problems, jaundice, and an increased chance of developing obesity or type 2 diabetes later in life. [21]

Choosing the Right Delivery Method for Women with Gestational Diabetes

The choice of delivery method for women with GDM depends on various factors, including blood glucose control, baby size, and overall pregnancy health. If your blood glucose levels are well managed, a vaginal delivery may be possible. However, suppose the baby is large due to excessive glucose in the bloodstream. In that case, a cesarean section may be recommended to reduce the risk of complications like shoulder dystocia or difficult delivery. Women with poorly controlled blood glucose or other complications may also require a C-section. Additionally, factors like high blood pressure, pre-eclampsia, and the baby’s well-being may influence the decision. Close monitoring of blood glucose levels and regular prenatal visits help determine the safest delivery method for both the mother and baby. [22]

1. Antihistamines

Since it is one of the most common symptoms of auto dermatitis, antihistamines are often recommended. They work by blocking histamine, a substance released by your immune system during an allergic reaction, which can cause itching. These can be helpful, especially at night, as they may also have a sedative effect to help with sleep when itching is severe. [17]

2. Phototherapy

Phototherapy (or light therapy) involves exposing the skin to controlled amounts of ultraviolet (UV) light under medical supervision. This treatment can help reduce inflammation and improve symptoms, particularly in severe cases of atopic dermatitis that don’t respond to topical treatments. It’s commonly used in cases where the condition is widespread and persistent. [18]

3. Antibiotics

Antibiotics are not needed for dermatitis, but with the cracks in the skin because of atopic dermatitis, there is a very high chance of infection. Atopic dermatitis is commonly associated with infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Managing these infections can help prevent the condition from worsening. [19]

4. Lifestyle Changes

Making lifestyle adjustments is crucial in managing atopic dermatitis. This includes avoiding known triggers like harsh soaps, certain fabrics (such as wool), and hot water. Using gentle, fragrance-free skin care products and wearing soft, breathable clothes can also help minimize irritation. Additionally, managing stress through relaxation techniques like meditation or yoga can prevent flare-ups since stress is a known trigger. [20]

Risk of Developing Diabetes after Gestational Diabetes

Women who have had GDM are at a higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes later in life. Even though blood glucose levels usually return to normal after pregnancy, the risk remains elevated. Studies show that women with GDM are about 7 times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes compared to those who didn’t have GDM. The risk is higher if they have poor blood glucose control during pregnancy, are overweight, or have a family history of diabetes. It’s important for women who have had GDM to continue monitoring their blood glucose levels and maintain a healthy lifestyle to reduce the risk of developing type 2 diabetes in the future. [23]

Postpartum Glucose Monitoring for Women with Gestational Diabetes: Timing and Importance

The American Diabetes Association recommends having a glucose test (usually a 2-hour OGTT) at 4 to 12 weeks postpartum to assess if diabetes persists. Follow-up tests should be done at least every 1 to 3 years to monitor for any changes in glucose metabolism. The idea is to check your blood glucose even after the pregnancy and even if your blood glucose levels return to normal because of the increased risk. [24–25]

Gestational Diabetes and Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome

If you have polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), you’re more likely to develop GDM than someone without it because of the similarity they share. Women with PCOS like GDM have insulin resistance, where the body has difficulty using insulin properly, increasing blood glucose levels. This insulin resistance can make it more difficult for women with PCOS to control their blood glucose during pregnancy, leading to a higher risk of GDM. Because of this higher risk, women with PCOS need to be watched closely for GDM during pregnancy. [26]

Questions to Ask Your Doctor

- Is it possible to manage gestational diabetes without medication?

- How long will I need to continue taking medication for gestational diabetes?

- What should I do if I forget to take my insulin shot?

- What should I do if my blood glucose is too high or too low?

- Could gestational diabetes of this pregnancy affect my future children in any way?

References

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes–2008. Diabetes Care. 2007 Dec 28;31(Supplement 1):S12–54.Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18165335/

- American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care [Internet]. 2010 Dec 30;33(Supplement_1):S62–9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2797383/

- Baz B, Riveline JP, Gautier JF. ENDOCRINOLOGY OF PREGNANCY: Gestational diabetes mellitus: definition, aetiological and clinical aspects. European Journal of Endocrinology. 2016 Feb;174(2):R43–51. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26431552/

- Usman TO, Goma Chhetri, Yeh H, H. Henry Dong. Beta-Cell Compensation and Gestational Diabetes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2023 Dec 1;299(12):105405–5. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38229396/

- Li G, Wei T, Ni W, Zhang A, Zhang J, Xing Y, et al. Incidence and Risk Factors of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Prospective Cohort Study in Qingdao, China. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2020 Sep 11;11. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/endocrinology/articles/10.3389/fendo.2020.00636/full

- Thompson D, Berger H, Feig D, Gagnon R, Kader T, Keely E, et al. Diabetes and Pregnancy. Canadian Journal of Diabetes. 2013 Apr;37:S168–83. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24070943/

- Thornton JM, Shah NM, Lillycrop KA, Cui W, Johnson MR, Singh N. Multigenerational diabetes mellitus. Frontiers in Endocrinology [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 19];14:1245899. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38288471/

- Zhang Y, Xiao CM, Zhang Y, Chen Q, Zhang XQ, Li XF, et al. Factors Associated with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Diabetes Research [Internet]. 2021 May 10 [cited 2022 Jan 3];2021:e6692695. Available from: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/jdr/2021/6692695/

- Rottenstreich M, Rotem R, Reichman O, Farkash R, Rottenstreich A, Samueloff A, et al. Previous non-diabetic pregnancy with a macrosomic infant – Is it a risk factor for subsequent gestational diabetes mellitus? Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2020 Oct;168:108364.Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32791161

- Yuen L, Wong V, Jincy Immanuel, Hague WM, Cheung NW, Teede H, et al. Ethnic Differences in Characteristics of Women Diagnosed with Early Gestational Diabetes: Findings from the TOBOGM Study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2024 Dec 6; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39657254

- ElSayed NA, McCoy RG, Grazia Aleppo, Kirthikaa Balapattabi, Beverly EA, Early B, et al. 6. Glycemic Goals and Hypoglycemia: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care [Internet]. 2024 Dec 9 [cited 2024 Dec 12];48(Supplement_1):S128–45. Available from: https://diabetesjournals.org/care/article/48/Supplement_1/S128/157561/6-Glycemic-Goals-and-Hypoglycemia-Standards-of

- Sobrevia L, Valero P, Grismaldo A, Villalobos-Labra R, Pardo F, Subiabre M, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the fetoplacental unit in gestational diabetes mellitus. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Molecular Basis of Disease [Internet]. 2020 Dec 1 [cited 2020 Nov 28];1866(12):165948. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32866635/

- Pota ÇE, Doğan ME, Bülbül GA, Sanhal CY, Pota A. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Evaluation of Retinochoroidal Microvascular Circulation Differences in Pregnant Women with Pregestational and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes: Official Journal, German Society of Endocrinology [and] German Diabetes Association [Internet]. 2024 Jun 6 [cited 2024 Jun 11]; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38843821

- Sacks DB, Arnold MA, Bakris GL, Bruns DE, Horvath AR, Åke Lernmark, et al. Executive Summary: Guidelines and Recommendations for Laboratory Analysis in the Diagnosis and Management of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2023 Jul 20;46(10):1740–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37471272

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Tests & Diagnosis for Gestational Diabetes | NIDDK [Internet]. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 2019. Available from: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/what-is-diabetes/gestational/tests-diagnosis

- Oskovi-Kaplan ZA, Ozgu-Erdinc AS. Management of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology [Internet]. 2021;1307:257–72. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32548833

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Managing & treating gestational diabetes [Internet]. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. 2019. Available from: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/diabetes/overview/what-is-diabetes/gestational/management-treatment

- American Diabetes Association. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003 Dec 23;27(Supplement 1):S88–90. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14693936/

- Valent AM, Barbour LA. Insulin Management for Gestational and Type 2 Diabetes in Pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2024 Jun 13; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38870526

- Bergel R, Hadar E, Toledano Y, Hod M. Pharmacological Management of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Current Diabetes Reports. 2016 Oct 17;16(11). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27752931/

- Oros Ruiz M, Perejón López D, Serna Arnaiz C, Siscart Viladegut J, Àngel Baldó J, Sol J. Maternal and foetal complications of pregestational and gestational diabetes: a descriptive, retrospective cohort study. Scientific Reports [Internet]. 2024 Apr 19 [cited 2024 May 12];14(1):9017. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-024-59465-x

- Will JS, Crellin H. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: Update on Screening, Diagnosis, and Management. American Family Physician [Internet]. 2023 Sep 1;108(3):249–58. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37725457

- Lo JC, Yang J, Gunderson EP, Hararah MK, Gonzalez JR, Ferrara A. Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus following Gestational Diabetes Pregnancy in Women with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Journal of Diabetes Research. 2017;2017:1–5. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29423416/

- Sacks DB, Arnold MA, Bakris GL, Bruns DE, Horvath AR, Åke Lernmark, et al. Guidelines and Recommendations for Laboratory Analysis in the Diagnosis and Management of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care [Internet]. 2023 Jul 20;46(10):e151–99. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37471273

- Pan ML, Chen LR, Tsao HM, Chen KH. Relationship between Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome and Subsequent Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Nationwide Population-Based Study. Wolfe A, editor. PLOS ONE. 2015 Oct 21;10(10):e0140544. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26488176/

- Okoshi C, Kyozuka H, Fukuda T, Yasuda S, Murata T, Isogami H, et al. Risk of gestational diabetes in women with PCOS based on body mass index: The Japan Environment and Children’s Study. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism [Internet]. 2024 May 4 [cited 2024 Jun 12];dgae293. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38703083