Highlights of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

- Hepatocellular carcinoma accounts for 75–85% of liver cancers and is a leading cause of cancer-related deaths.

- The most important risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma is chronic liver disease, particularly hepatitis B or C infection, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

- About 30% of the cases of hepatocellular carcinoma are due to the consumption of a heavy amount of alcohol.

- A liver transplant is not the only treatment option for hepatocellular cancer, and it is an option only for a few people.

- Omega-3 fatty acids, specifically alpha-linolenic acid, have been shown to stop the growth of HCC cells, suggesting a potential role in suppressing the progression of HCC.

What is Hepatocellular Carcinoma?

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver malignancy of the liver and a significant cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide. It accounts for approximately 75-85% of all liver cancers. It is estimated that there will be over one million cases by 2025. [1]

The disease is most common in East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa due to widespread hepatitis B infection. In Western countries, its rates are rising because of the increasing prevalence of metabolic syndrome and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). [1]

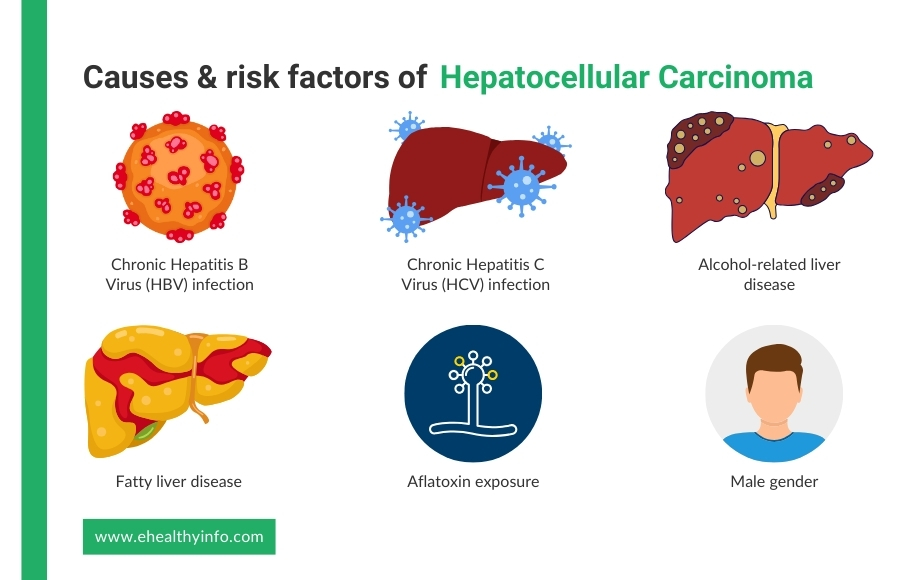

Risk Factors of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

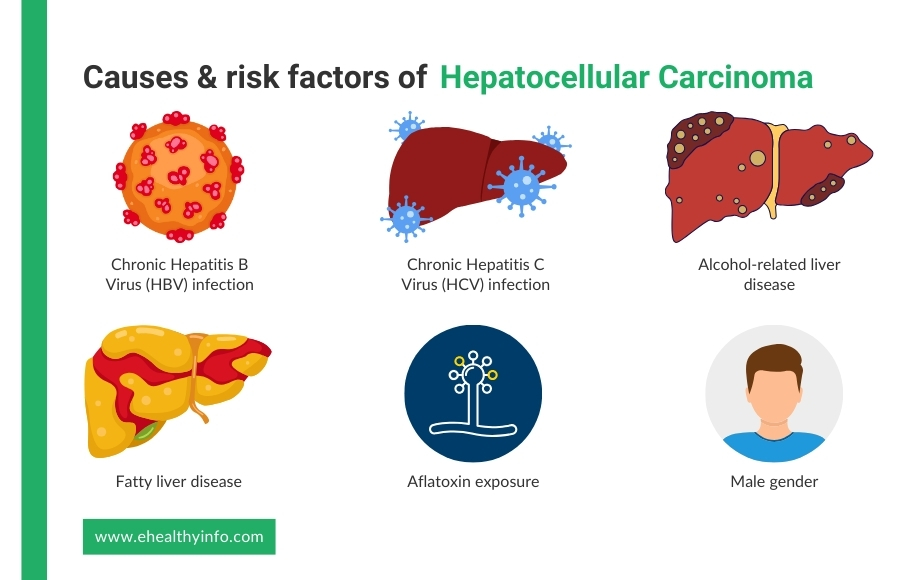

Several well-established risk factors contribute to the development of HCC, including:

1. Chronic Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a significant cause of HCC globally. Chronic HBV infection leads to persistent liver inflammation, fibrosis, and eventual cirrhosis, creating a high-risk environment for carcinogenesis. HBV is particularly oncogenic due to its ability to integrate into the host genome. East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa report a disproportionately higher HCC incidence, and those are the regions with a higher prevalence of HBV. [2]

2. Chronic Hepatitis C Virus (HCV) Infection

Hepatitis C virus (HCV)-associated cirrhosis also accounts for a significant proportion of HCC cases in Western countries and Japan. Of patients infected with the hepatitis C virus, about 80% progress to chronic hepatitis, with almost 20% developing cirrhosis. With chronic inflammation and fibrosis, HCV induces long-term liver damage and hepatocellular carcinoma. [3]

3. Alcohol-Related Liver Disease

Chronic heavy alcohol consumption is a well-established risk factor for HCC, with 30% of the cases attributed to it. Alcohol causes liver damage through mechanisms such as oxidative stress, inflammation, DNA damage, and direct hepatotoxicity. This leads to cirrhosis, ultimately increasing the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. [4]

4. Fatty Liver Disease

NAFLD, especially its severe form, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), is an emerging risk factor for HCC. Around 60% of patients over 50 with diabetes or obesity are believed to have NASH with advanced fibrosis. Linked to metabolic syndrome, obesity, and type 2 diabetes, NAFLD and NASH contribute to progressive liver inflammation, fibrosis, and cancer development. With NAFLD becoming more common, particularly in developed countries, it is expected to become a leading cause of HCC. [5]

5. Aflatoxin Exposure

Aflatoxin is a carcinogenic toxin produced by Aspergillus species in improperly stored grains and is a significant risk factor in regions with poor food storage practices. Aflatoxin induces mutations in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene, accelerating the pathogenesis of HCC. [6]

6. Male Gender

HCC is found to be more common in men than in females; it occurs about two to four times more often in men. [1]

7. Disease Conditions

Disorders like hereditary hemochromatosis, Wilson’s disease, α-1 antitrypsin disease, glycogen storage disease, and porphyrias predispose to chronic liver damage and subsequent HCC. [7]

Pathophysiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

HCC develops when liver cells become damaged over time and start growing abnormally. Long-term liver injury from conditions like hepatitis B or C, fatty liver disease, or excessive alcohol use can lead to ongoing inflammation and scarring. As the liver tries to repair itself, some cells may grow uncontrollably, leading to cancer. Even chronic inflammation, genetic changes in the cells like the mutation of genes that suppress cancer, and the buildup of harmful substances in the liver contribute to this process. Over time, these cancerous cells form a tumor that can spread to other parts of the liver or beyond. [8–9]

Clinical Features of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

HCC often presents with a wide range of clinical features, depending on the disease stage and underlying liver conditions. In its early stages, HCC is frequently asymptomatic. As the disease progresses, more specific symptoms and signs may develop.

1. Unexplained Weight Loss

Many people with HCC lose weight without trying. This happens because the cancer affects the body’s metabolism, making it harder to absorb nutrients. As the disease progresses, weight loss becomes more noticeable due to reduced appetite and muscle wasting. [10]

2. Loss of Appetite and Feeling Full Quickly

Even after eating a small amount, you may feel full or uninterested in food. This is because liver cancer can affect digestion and slow down the movement of food in the stomach. Over time, this lack of appetite leads to weakness and malnutrition. [10]

3. Abdominal Pain or Discomfort

Pain in the upper right side of the abdomen is common and may start as mild discomfort before worsening. The growing tumor pressures surrounding organs and nerves lead to a persistent dull or sharp pain. Sometimes, the pain may radiate to the back or right shoulder. [10]

4. Swelling in the Abdomen (Ascites)

The liver helps regulate fluid balance in the body. When it is damaged by cancer, fluid builds up in the belly, causing noticeable swelling and tightness. This condition, is called ascites, can make it difficult to breathe or move comfortably. It is often a sign that the cancer is affecting liver function significantly. [11]

5. Yellowing of the Skin and Eyes (Jaundice)

The liver processes bilirubin, a substance that gives bile its yellow color. When liver function declines due to cancer, bilirubin accumulates in the blood, causing the skin and eyes to turn yellow. Jaundice is often accompanied by dark-colored urine and pale stools, which indicate poor bile flow. [11]

6. Fatigue and Weakness

Many people with HCC feel extremely tired, even after resting. This happens because the liver filters toxins, produces proteins, and stores energy. When the liver is damaged, the body struggles to function properly, leading to persistent fatigue and reduced stamina. [12]

7. Easy Bruising or Bleeding

The liver produces clotting factors that help stop bleeding. When HCC affects liver function, blood does not clot as well, leading to frequent bruising, nosebleeds, and bleeding gums. Even minor injuries may result in excessive bleeding. [11]

8. Lump or Mass in the Upper Right Abdomen

As the tumor grows, it may form a hard lump under the ribs on the right side. Some people may feel this mass when lying down or pressing on the area. The presence of a lump often indicates that the tumor has become large. [12]

9. Fever and General Feeling of Being Unwell

Some people with HCC experience recurring fevers, chills, and a general sense of discomfort. This happens because the body recognizes the cancer as abnormal and responds with inflammation. The immune system’s reaction can cause flu-like symptoms, adding to overall weakness. [12]

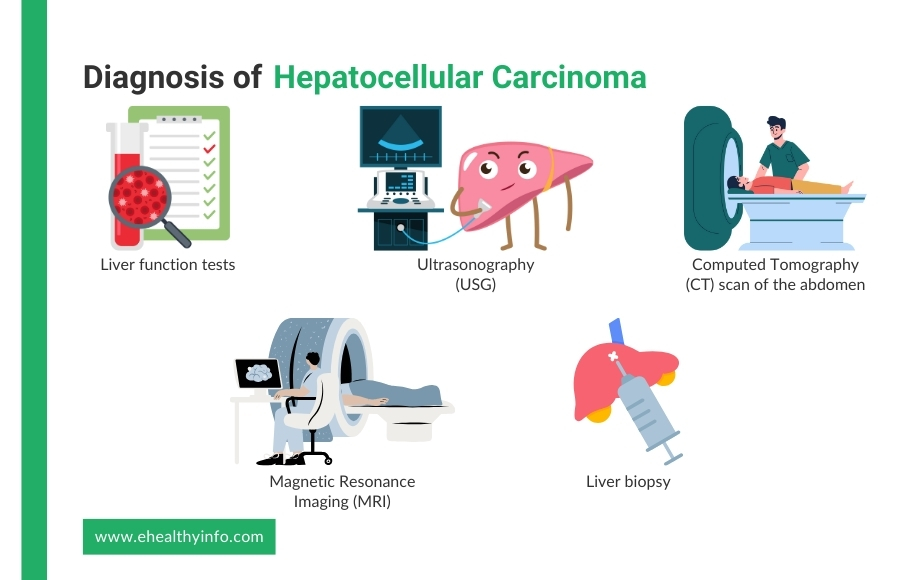

Diagnosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

HCC is diagnosed through clinical evaluation, imaging modalities, laboratory tests, and sometimes by histological confirmation.

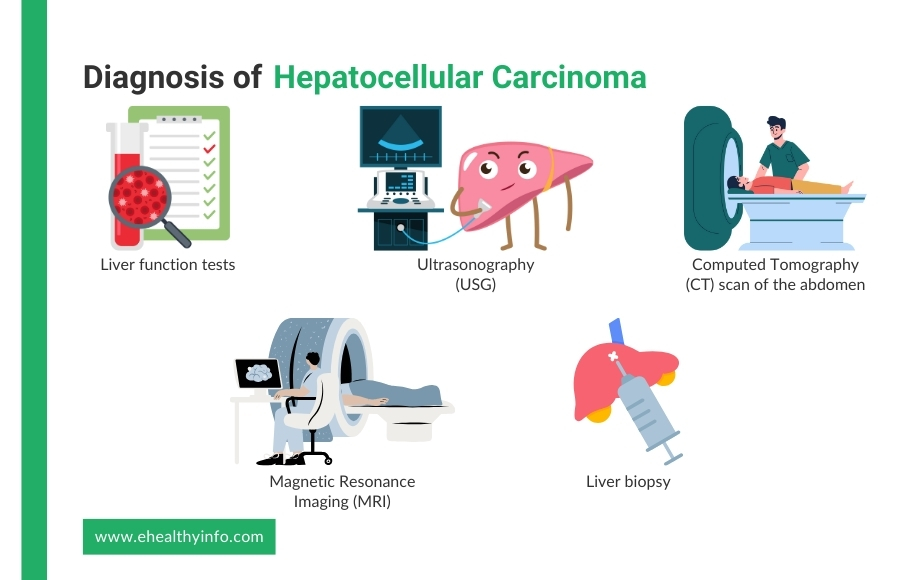

Clinical and Laboratory Assessment

- Liver Function Tests: Liver function tests play an important role in both the diagnosis and management of HCC. Key liver function tests include the measurement of serum bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase, albumin, and prothrombin time. [13]

- Biomarkers: Elevated alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels are commonly used for initial screening, but its sensitivity and specificity are low. Other markers include des-gamma-carboxy prothrombin (DCP), and these biomarkers are combined with imaging for both surveillance and diagnosis. [13]

Imaging

- Ultrasonography (USG): USG is a commonly used imaging tool for diagnosing HCC. It is non-invasive, widely available, and helps detect liver tumors early, especially in high-risk individuals. Sound waves create images of the liver during the scan, allowing doctors to identify abnormal growths or suspicious lesions. Doppler ultrasound can also assess blood flow within the liver and detect changes in blood vessels associated with HCC. In patients with cirrhosis or chronic liver disease, regular USG screenings help monitor liver health and catch cancer in its early stages. If a suspicious lesion is found, further tests like contrast-enhanced ultrasound, CT scans, or MRI may be needed to confirm the diagnosis. [14]

- Computed Tomography (CT) Scan of the Abdomen: CT scan is the primary imaging modality for diagnosing HCC. A CT scan is an advanced imaging test that provides detailed cross-sectional images of the liver, helping to detect HCC. It is often performed with contrast dye, which enhances the visibility of liver tumors. [15]

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI is a highly sensitive test for diagnosing HCC, especially in detecting smaller tumors and distinguishing them from benign liver lesions. MRI uses powerful magnets and radio waves to create detailed liver images. Additionally, MRI provides better soft tissue contrast, helping clearly identify tumor characteristics. It is particularly useful in patients with liver cirrhosis or when CT findings are inconclusive. [16]

Liver Biopsy

A liver biopsy involves taking a small tissue sample from the liver to examine under a microscope. It is usually performed when imaging tests like ultrasound, CT, or MRI do not diagnose clearly. The procedure uses a thin needle inserted through the skin, guided by imaging to target the suspicious area. A pathologist then examines the sample to check for cancerous cells. While a biopsy is the most definitive way to confirm HCC, it is not always necessary if imaging findings are characteristic. However, it carries small risks, such as bleeding or infection, and is usually reserved for cases where the diagnosis remains uncertain. [13]

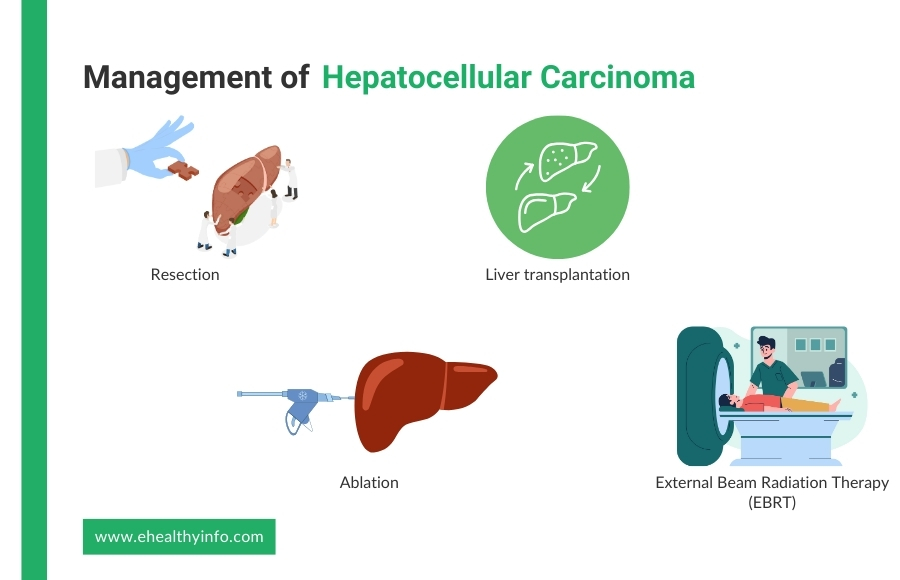

Management of Hepatocellular Carcinoma

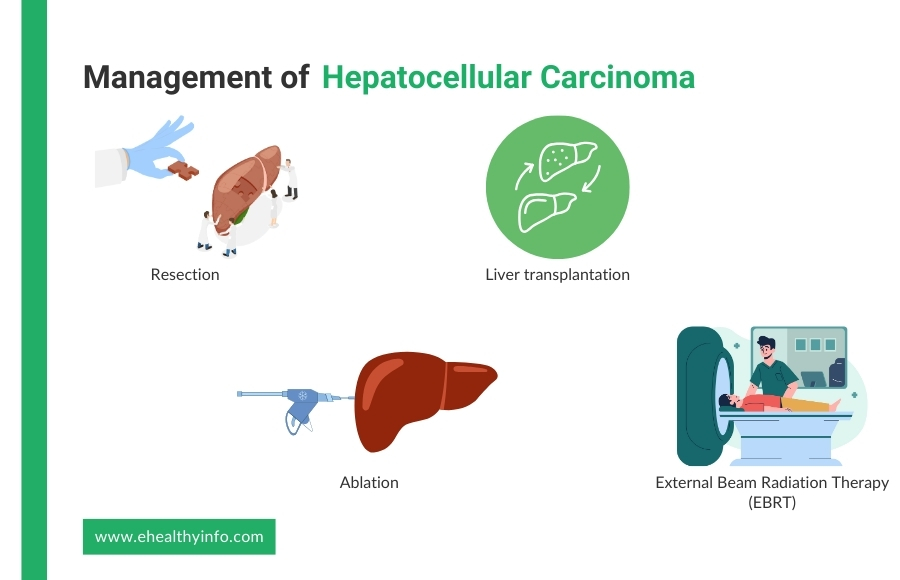

The treatment options for managing HCC are tailored to the patient’s liver function and stage of the disease.

Surgical Therapies

- Resection: Surgical resection is a treatment option for liver cancer when the tumor is confined to the liver and there is good liver function without significant cirrhosis. The procedure involves removing the cancerous part of the liver while preserving as much healthy tissue as possible. It is typically performed in patients with well-preserved liver function and no signs of widespread disease. Surgery offers the best chance for long-term survival, but it is not suitable for all patients, especially those with severe liver damage. After resection, regular follow-up is needed to monitor for recurrence, as HCC can return even after successful surgery. [17]

- Liver Transplantation: Liver transplantation is a treatment option for HCC in patients who meet specific criteria that help determine eligibility based on tumor size and number. This procedure involves replacing the diseased liver with a healthy donor liver, treating both the cancer and underlying liver disease, such as cirrhosis. It offers the best chance for long-term survival and a lower risk of cancer recurrence compared to resection. However, organ availability is limited, and patients may need to wait on a transplant list. After transplantation, lifelong immunosuppressive medications are required to prevent organ rejection. [18]

Locoregional Therapies

- Ablation: Ablation is a minimally invasive treatment for HCC mainly used for small tumors in patients who are not candidates for surgery or transplantation. The most common methods include radiofrequency and microwave ablation, which use heat to destroy cancer cells. Ablation is effective for tumors smaller than 3 cm and can help control cancer growth, especially in patients with liver disease. The procedure is done through a needle inserted into the tumor under imaging guidance, such as ultrasound or CT scan. [19]

- Transarterial Chemoembolization (TACE): TACE is a targeted treatment for HCC that helps slow tumor growth in patients not candidates for surgery or liver transplantation. The procedure involves injecting chemotherapy drugs directly into the blood vessels that supply the tumor, followed by blocking these vessels with tiny particles to cut off the tumor’s blood supply. This dual action helps deliver high-dose chemotherapy to the cancer while starving it of oxygen and nutrients. TACE is commonly used for intermediate-stage HCC or to shrink tumors before surgery or transplantation. It is performed through a catheter inserted into the artery and guided to the liver using imaging techniques. Side effects of TACE may include post-procedure pain, fever, and temporary liver function changes, but the procedure can be repeated if necessary to control tumor progression. [20]

- Transarterial Radioembolization (TARE): TARE is a targeted treatment for HCC that delivers tiny radioactive beads directly into the tumor’s blood supply. Unlike TACE, which uses chemotherapy and blocks blood flow, TARE uses radiation to destroy cancer cells while allowing some blood flow to continue. This can benefit patients with larger tumors or portal vein involvement, where TACE may be less effective. The procedure involves injecting radioactive microspheres into the liver artery, which emit radiation over time, leading to gradual tumor shrinkage with fewer side effects compared to TACE. While TACE is preferred for intermediate-stage HCC, TARE is often considered for more advanced cases or when patients cannot tolerate repeated TACE sessions. [21]

- External Beam Radiation Therapy (EBRT): EBRT is a non-invasive treatment for HCC that uses high-energy X-rays to target and destroy cancer cells. It is especially useful for patients who are not candidates for surgery, liver transplantation, or other local treatments like TACE or ablation. EBRT is delivered from outside the body, focusing radiation precisely on the tumor while minimizing damage to healthy liver tissue. Advanced techniques like stereotactic body radiotherapy allow for high-dose radiation in fewer sessions, improving effectiveness while reducing side effects. EBRT is often considered for patients with large tumors, vascular invasion, or those with pain due to tumor growth. It can also be used in combination with other therapies to improve outcomes. [22]

Systemic Therapies

Systemic therapies for HCC include targeted therapy and immunotherapy, which are used when surgery or local treatments aren’t an option. Targeted drugs like sorafenib and lenvatinib block cancer growth and blood vessel formation, while second-line options like regorafenib and cabozantinib help slow progression. Immunotherapy, such as atezolizumab with bevacizumab or nivolumab, boosts the immune system to fight cancer. These treatments can improve survival but may cause side effects like fatigue, high blood pressure, or immune-related reactions. The choice depends on liver function, tumor stage, and overall health. [23]

Omega-3 fatty acids and Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Omega-3 fatty acids, found in foods like fish, flaxseeds, and walnuts, have been studied for their potential role in managing HCC. These healthy fats possess anti-inflammatory properties, which may help reduce liver inflammation, a key contributor to liver damage and HCC development. Studies have shown that omega-3 fatty acids, specifically alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), have been shown to stop the growth of HCC cells through some sort of signalling pathway, suggesting a potential role for ALA in suppressing HCC progression. However, more research is needed to understand their role in HCC management. [24]

Questions To Ask Your Doctor

- What lifestyle changes or dietary adjustments should I make during treatment?

- What if I don’t want a liver transplant?

- Are there any clinical trials available for liver cancer?

- Are there any natural methods available for treatment?

- What are the possible side effects of the recommended treatments, and how can they be managed?

- Will my children get this condition from me?

References

- McGlynn KA, Petrick JL, El‐Serag HB. Epidemiology of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatology. 2020 Apr 22;73(S1). Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7577946/

- Wong GLH. Risk prediction of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma in the era of antiviral therapy. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2013;19(39):6515. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3801362/

- Bucci L, Garuti F, Camelli V, Lenzi B, Farinati F, Giannini EG, et al. Comparison between alcohol- and hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical presentation, treatment and outcome. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2015 Dec 14;43(3):385–99. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26662476/

- Ganne-Carrié N, Nahon P. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the setting of alcohol-related liver disease. Journal of Hepatology. 2019 Feb;70(2):284–93. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30658729

- Rinella ME. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. JAMA. 2015 Jun 9;313(22):2263. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26057287/

- Cai P, Zheng H, She J, Feng N, Zou H, Gu J, et al. Molecular Mechanism of Aflatoxin-Induced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Derived from a Bioinformatics Analysis. Toxins [Internet]. 2020 Mar 23 [cited 2021 Nov 4];12(3):203. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7150856/

- Jophlin L, Singal AK, Ramón Bataller, Wong RJ, Sauer BG, Terrault NA, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2023 Sep 1;119(1):30–54. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38174913

- Llovet JM, Kelley RK, Villanueva A, Singal AG, Pikarsky E, Roayaie S, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nature Reviews Disease Primers [Internet]. 2021 Jan 21;7(1):1–28. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41572-020-00240-3

- Khemlina G, Ikeda S, Kurzrock R. The biology of Hepatocellular carcinoma: implications for genomic and immune therapies. Molecular Cancer. 2017 Aug 30;16(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28854942

- Di Bisceglie AM. Epidemiology and Clinical Presentation of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 2002 Sep;13(9):S169–71. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12354833

- Hepatocellular carcinoma – Symptoms, diagnosis and treatment | BMJ Best Practice [Internet]. bestpractice.bmj.com. Available from: https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/369

- Bucci L, Garuti F, Camelli V, Lenzi B, Farinati F, Giannini EG, et al. Comparison between alcohol- and hepatitis C virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical presentation, treatment and outcome. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2015 Dec 14;43(3):385–99. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26662476/

- Benson AB, D’Angelica MI, Abbott DE, Anaya DA, Anders R, Are C, et al. Hepatobiliary Cancers, Version 2.2021, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2021 May;19(5):541–65. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34030131

- Liava C, Emmanouil Sinakos, Elissavet Papadopoulou, Lamprini Giannakopoulou, Stamatia Potsi, Anestis Moumtzouoglou, et al. Liver Imaging Reporting and Data System criteria for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in clinical practice: A pictorial minireview. 2022 Aug 28 [cited 2023 Jun 25];28(32):4540–56. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9476877/

- Nadarevic T, Giljaca V, Colli A, Fraquelli M, Casazza G, Miletic D, et al. Computed tomography for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in adults with chronic liver disease. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews [Internet]. 2021 Oct 6;10:CD013362. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8493329/

- Nadarevic T, Colli A, Giljaca V, Fraquelli M, Casazza G, Manzotti C, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in adults with chronic liver disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2022 May 6;2022(5). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35521901

- Civan JM. Liver Transplantation for HCC: The Milan Criteria. Springer eBooks. 2016 Jan 1;1–20. Available from: https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-319-05543-5_11-1

- Neha Jakhete, Majeed NA, Maluf D, Shetty K. The Role of Liver Transplantation in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clinics in Liver Disease [Internet]. 2024 Oct 30 [cited 2025 Mar 1];29(1):73–85. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39608959

- Niemeyer DJ, Simo KA, Iannitti DA, McKillop IH. Ablation therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: past, present and future perspectives. Hepatic Oncology. 2014 Jan;1(1):67–79. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6114009/

- Thornton LM, Abi-Jaoudeh N, Lim HJ, Malagari K, Spieler BO, Kudo M, et al. Combination and Optimal Sequencing of Systemic and Locoregional Therapies in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Proceedings from the Society of Interventional Radiology Foundation Research Consensus Panel. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR [Internet]. 2024 Jun;35(6):818–24. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/38789204

- Berardi G, Guglielmo N, Alessandro Cucchetti, Usai S, Colasanti M, Meniconi RL, et al. Transarterial Radioembolization Can Downstage Intermediate and Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma to Liver Transplantation. Transplantation [Internet]. 2024 Sep 17 [cited 2025 Mar 1];109(1):e54–63. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39285520

- Dudzinski SO, Newman NB, McIntyre J, Engineer R, Sanford NN, Wo JY, et al. Emerging evidence-based role for external-beam radiation therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. The Lancet Gastroenterology & hepatology [Internet]. 2025 Feb 1 [cited 2025 Mar 1]; Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39993402

- Lei J, Yang S, Chen B, Zhang L, Yan T, Yang G, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors Alone or Combination with Programmed Death-1 Inhibitors in Treating of Hepatitis C-Related Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Journal of Hepatocellular Carcinoma [Internet]. 2023 Mar 1 [cited 2024 Nov 26];Volume 10:357–67. Available from: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9987323/

- Feng S, Xie X, Chen C, Zuo S, Zhao X, Li H. Alpha-linolenic acid inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell growth through Farnesoid X receptor/β-catenin signaling pathway. Nutrition & Metabolism [Internet]. 2022 Aug 23 [cited 2025 Mar 1];19(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35999582